Iran's constant tipping point

It’s the largest uprising since the 1979 revolution. But aside from the scale of the bloodshed, what's new?

As someone with Iranian heritage, I’m periodically asked about whatever is happening in Iran at that moment, and whether this time, things will be different. Would the Green Movement that brought three million people onto the streets to protest Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s 2009 landslide election, change Iranian politics? Would the Woman, Life, Freedom movement, which inspired huge solidarity protests around the world, end compulsory hijab laws? And will this year’s protests, reportedly the largest — and bloodiest — since 1979, finally bring down the Islamic Republic?

The short answer is no. This is not because Iranians lack courage or imagination. It is because Iran has been caught in a web of foreign interests and internal rifts for at least 100 years. As long as this continues to spin, this fascinating country, as culturally rich as it is politically volatile, will not see lasting harmony.

20th century Iran: A perpetual tug of war

At the start of the 20th century when Iran was still known as Persia, its Shah was Mozzaffar-al-Din, a man of extravagant tastes. Such was his love of luxury that the country spiralled into debt after borrowing heavily from Britain and the Soviet Union. To appease a growing revolt, he agreed to establish the country’s first constitution in 1906, allowing him to stay in power as a figurehead while passing most political decision-making to parliament.

Not everyone was happy. Religious conservatives thought the new constitution ‘un-Islamic’, while overseas governments worried about their economic investments with a less powerful Shah. Over the next 15 years these tensions continued, in no small part aided by rival British and Soviet forces occupying parts of Persia. There were frequent uprisings, at least one episode of martial law, and several changes of Shah.

By 1921 Britain was worried enough about the Soviet Union’s growing influence to support ambitious army officer Reza Khan Pahlavi to stage a coup. After declaring himself the new ruler he set about modernising the country’s infrastructure with better healthcare, education and transport systems, but to the chagrin of his Western allies he also wanted to nationalise the oil industry. These special relationships soured, and after he refused to expel German workers during World War II, it was once again decided that it was time for change. His son Mohammed Reza became the next Shah in 1941, and Pahlavi senior was forced into exile.

The younger Shah took a very different approach to modernisation, inviting companies like Pepsi, Citroën, American Motors and Volkswagen to open plants, giving away huge chunks of the profits (and complete immunity from arrest to US soldiers and employees).1

However foreign investment enabled him to continue his father’s reforms with the ‘White Revolution’: these included redistributing land to agricultural workers; giving women the right to vote for the first time; making education free and compulsory to reduce illiteracy; and introducing social security benefits.

Iran’s cities transformed: new highways, high-rise buildings and modern housing complexes sprang up thanks to a thriving industrial sector. Tehran became a cosmopolitan hub with cafés, cinemas, universities and American and French schools. The city experienced its own version of the Swinging 60s along with its fashion (it still surprises people to know that none of the women in my family ever had to wear a headscarf to cover their hair).

That’s not to say that Iran had suddenly become a utopia. As strongmen do when intent on reshaping a nation in their own image, the Shah outlawed political parties and imposed strict media censorship to eliminate criticism of the monarchy. (Western powers also played a role: since World War II they had closely monitored the press, suppressing material they deemed harmful to the interests of the occupying forces.)

“The population is split between religious loyalty and the thirst for freedom and greater communication with Western countries. It is quite possible that the younger generations of today, who are currently rebelling against the authorities will one day tear down the theocracy that is Iran, and the structure of the government will once again change.”

The Influence of Politics in the Music of Iran (written by me in 2005)

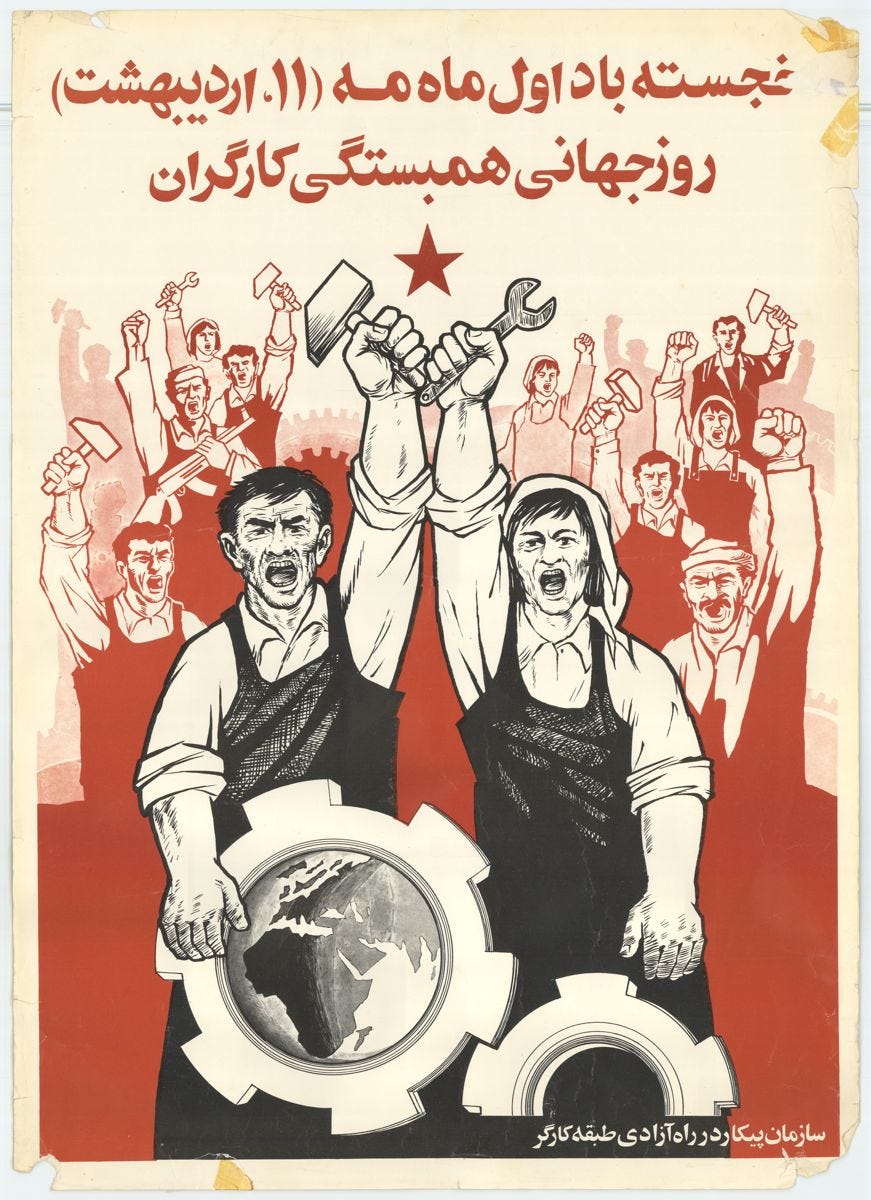

Meanwhile, not everyone was benefiting from the economic boom. Increased prosperity led to a growing middle class, but the Pahlavis and the wealthy elite enjoyed its riches as a large portion of the population still lived below the poverty line. Religious hardliners resented the rapid pace of change and Western cultural influence, fearing their power was slipping away. Workers, students and Marxist groups couldn’t bear the Shah’s lavish excesses in the face of the living conditions of ordinary Iranians. Some protest groups like the People’s Fedai were armed guerrillas, but all were united in their desire to abolish the monarchy.

Protests spread nationwide, and the Shah responded with impunity. His SAVAK (Bureau for Intelligence and Security of the State) army ran surveillance operations, made thousands of arrests and carried out acts of torture and even murder to silence dissent. According to multiple reports, it was taught these tactics by the CIA. The White Revolution, so-called because it was intended to happen without violence, had become anything but.

This perfect storm led to the rise of the Ayatollah Khomeini, an ascetic cleric who seemed to promise a fairer, more humble form of leadership. After the Shah lost the support of the military the regime fell, and Khomeini became the official leader of the newly named Islamic Republic of Iran.

All ties with Western countries were severed, and the industry was nationalised. Western films, books and “corrupting” pop music were banned. The workers, students and middle class intellectuals who helped Khomeini secure victory were all pushed aside once he took power, and the SAVAK would be replaced with an equally brutal Islamic Revolutionary Guard.

After the revolution: Struggle in a new hat

The state censorship and oppression of Iran’s post-revolutionary regime (not least of women) are well-known. Yet outside Iran, there is a tendency to flatten the country’s history into the glamour of the pre-revolutionary era versus a present defined solely by religious fanaticism. Proclamations to “liberate Iranian women” are often thinly veiled propaganda.

Ever since 1979, Iran’s leadership has swayed lightly between the marginally more moderate — like presidents Rafsanjani and Khatami — to hardliners like Ahmadinejad. Periodic uprisings have erupted in response to repression or economic hardship, but none have produced a unified opposition or a credible alternative leader.

The son of the last Shah, Reza Pahlavi, who has occasionally commented on Iran’s events from exile in Washington DC, has emerged the boldest he’s ever been with the latest revolt, urging people around the world to take to the streets to pressure the international community into taking action. Backed rhetorically by the US and Israeli administrations, this may be his greatest chance to become king. After all, it would not be the first time economic suffering becomes opportunity (consider the sanctions imposed by the very same powers parroting about women’s freedom).

Ironically, research published in September 2025, months before the current unrest, suggested that the sanctions had “destroyed” the middle class, and by doing so “cleared the field for the very hardliners they claimed to oppose. The regime could now plausibly blame all suffering on a foreign enemy, while its control over a crippled economy gave it even more power over a desperate population.”

Given what we know, I would counter that this was the intended aim. The question then, is not whether there will be regime change — it’s who benefits most from Iran’s instability.

One particular controversial deal allowed funds from Iranian oil companies to be shared between the US, the UK, France and Holland for 25 years, with no profits going to Iran.

Sidenote: Today’s oil giant BP was once known as the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, a target for prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh to renegotiate a better deal for Iran. This was much to the dissatisfaction of the British government, who lobbied the US and friends in the Iranian government to remove him. Mossadegh has the honour of being the first elected leader to be overthrown by the CIA in 1952.