What you're not hearing about AI

Is the story you're getting one of innovation and progress, or power and control?

We’ve handed over huge parts of our lives to AI. It writes our emails, gives us recipes and finds us gift ideas; our online searches open with AI-generated summaries, and the majority of our interactions with banks, shops and doctors’ offices are with chatbots rather than humans. In just three years since ChatGPT launched, we’ve gone all-in on this exciting, powerful new technology that has promised to make our lives better, but without questioning the motives of who is behind it or considering its long term consequences.

You have probably heard warnings over the reliability of ChatGPT’s information, especially as almost half its data comes from blogs, Wikipedia and discussion forums like Reddit. However this doesn’t seem to be deterring people from using it for important stuff like medical advice. A study by Stanford University School of Medicine assessed 15 different AI models including OpenAI, Anthropic and Google, asking them hundreds of questions like which drugs are safe to combine. Less than 1% gave responses that included a disclaimer to say that AI was not qualified to give accurate medical information.

What you may not know, is that in 2023 they almost always did, and researchers think that getting rid of them was a tactical decision to gain people’s trust, precisely because the answers are so frequently wrong.

Jurgita Lapienytė, editor-in-chief at Cybernews, warns this is dangerous “especially for people who are lonely or have psychological conditions. They over-rely on chatbots and sometimes treat them as their friends.”

This has led to situations like the man who developed a serious psychiatric condition after taking ChatGPT’s advice to replace salt in his diet with sodium bromide.

And we may all be more susceptible than we think. Lapienytė says that AI can “trick” even savvy people into trusting its content, for example by providing links to sources to make it appear credible, but that aren’t actually real. “We trust articles that have footnotes leading you to another source, but do we check those sources? Sometimes we do not. We knew that chatbots hallucinate when ChatGPT arrived, but the fact that they are also hallucinating links is something we aren’t used to just yet.”

Bias, what bias?

You might be aware of algorithmic bias, when an answer or outcome is discriminatory because the data isn’t diverse enough or it reflects the biased beliefs of the developers. Like when ChatGPT advised women to ask for a lower salary when applying for the same job as a man. “It’s taking data that says men earn more,” Lapienytė explains. “All these large language models are trained on databases and documents that are biased because they are built by us.

“When it comes to minorities, or people of colour, or any other group of people historically excluded or not as well represented in the databases, we risk reinforcing real world problems and biases that we’ve had for centuries,” she adds.

Author and academic Safiya Noble has been warning about the harms of allowing algorithms to guide our decisions since publishing her groundbreaking book ‘Algorithms of Oppression’ back in 2018. In the book she draws clear links between our growing dependence on tech and deepening inequality, citing (among others) the example of online property listing site Zillow. By using various data points and machine learning techniques, it recommends properties to users based on their preferences. It’s a great concept in theory, but Noble argues tools like this are creating a “resegregation” of the housing and educational markets, because the data assumes that “good” neighbourhoods are affluent, historically white areas.

She wrote that in the future “it will become increasingly difficult for technology companies to separate their systematic and inequitable employment practices, and the far-right ideological bents of some of their employees, from the products they make for the public.” Which, in case you hadn’t noticed, is where we are today.

The broligarchy

As the whistleblower in the Facebook–Cambridge Analytica scandal, Christopher Wylie knows the inner workings of Big Tech better than most. At a recent media and human rights conference he recalled attending a party of Silicon Valley moguls where discussions centred on creating a superintelligence network to replace governments, how to live forever, and how to survive the eventual collapse of democracy. While this sounds like the premise of a sci-fi movie, they are real plans being made by some of the world’s most powerful men.

Wylie warned of the tech sector’s growing power and called the push to replace staff with AI as a way to cut costs and make efficiencies a “political choice.”

He also questioned why we aren’t paying more attention to the actions of people who so openly express admiration for fascist ideologies.

Consider Peter Thiel, co-founder of Paypal and Palantir, and a major investor in Facebook. Supremely critical of diversity, science and government, he believes that fascism is “more innocent” than communism, and that Greta Thunberg is “a shadow of the antichrist”. He believes institutions — formed of people with empathic, decision-making capabilities — should be replaced with blockchain technology. He also has some interesting views on women’ s suffrage:

“The 1920s were the last decade in American history during which one could be genuinely optimistic about politics. Since 1920, the vast increase in welfare beneficiaries and the extension of the franchise to women — two constituencies that are notoriously tough for libertarians — have rendered the notion of “capitalist democracy” into an oxymoron.”

But instead of confining Thiel and his nonsensical ideas to the obscurity they deserve, Palantir is awarded contracts to handle our most sensitive personal information, including the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) patient data and databases for US national security agencies.

Wylie says that Silicon Valley pushes the narrative that people in government are too stupid to operate information systems without its expertise, and so Thiel, Elon Musk and their peers have been elevated to the status of saviours of civilisation — when they are in fact, barely stable narcissists.

Flooding the zone

Much has been written about Elon Musk’s rebranding of Twitter, which involved removing its trust and safety team, reviving accounts that had been banned for hate speech, and launching Grok, the chatbot infamous for spreading disinformation.

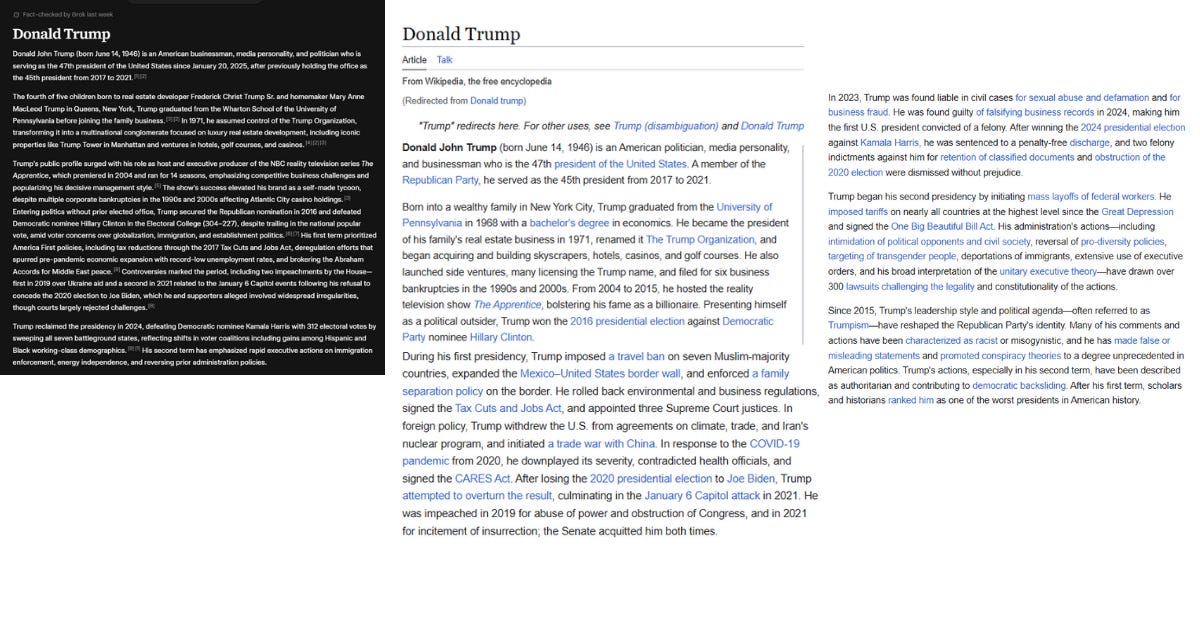

More recently he released Grokipedia, a version of Wikipedia covering the same topics, but filtered through Musk’s distinctively propagandist worldview. Take for instance its summary of Donald Trump, which is significantly shorter than Wikipedia’s (take a guess at what has been left out).

We may not take Grokipedia seriously, but we should pay attention to fact-checker and tech expert Alexios Mantzarlis, who quotes an infamous line from Steve Bannon:

“The question, however, is whether Grokipedia can succeed not as an alternative to Wikipedia but as a means to delegitimise it. “Flooding the zone with shit” as a strategy doesn’t necessarily seek to replace institutions of collective knowledge generation; it seeks to deface them.”

Like his fellow techno-libertarians, Musk shares similar views on shrinking the state. He was given a golden opportunity to practise this on the US government when he formed the Orwellian-sounding Department of Government Efficiency (also known as DOGE, sharing its acronym with cryptocurrency Dogecoin — never let it be said that billionaires don’t have a sense of humour).

We know Silicon Valley hates any form of regulation that might hinder its technological innovations, but if tech elites hate governments so much why invest such huge amounts of time and money into political campaigns?

“The tech industry has sought to reshape society to enable more widespread deployment of the technologies it builds and profits from, often contributing to the degradation of our social, political, and economic lives,” states a report by the AI Now Institute.

DOGE ended a bunch of government grants and cut thousands of jobs with the stated objective of saving taxpayers’ dollars. However the current position of the US economy suggests this has been ineffectual at best, while experts say that government services have worsened. At least in a multimillion dollar deal announced in July, all federal government departments and offices can now make use of Grok for Government’s suite of AI tools.